David Owen Dodd

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaJump to: navigation, search

David Owen Dodd

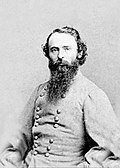

The only known photograph of Dodd

Born November 10, 1846(1846-11-10)

Lavaca County, Texas, USA

Died January 8, 1864 (aged 17)

Little Rock, Arkansas, USA

Known for Hanged as a spy in the American Civil War

Religion Baptist

David Owen Dodd (November 10, 1846 – January 8, 1864) was an American 17 year-old who was tried, convicted and hanged as a Confederate spy in the American Civil War.[1]

In December 1863, Dodd carried some letters to business associates of his father in Union-held Little Rock, Arkansas. While traveling home to Confederate-held Camden, Arkansas, he mistakenly re-entered Union territory. Found to be without a pass, Union soldiers questioned him and discovered that he was carrying a notebook with the locations of Union troops in the area. He was arrested and tried by a military tribunal, with little defense offered for his actions. The tribunal found him guilty of spying and he was hanged for his crime in January 1864. Though Dodd did not reveal the source of the information, a 15-year old girl named Mary Dodge and her father were summarily escorted back to their home in Vermont. These events have led to David Owen Dodd being called the "Boy Martyr of the Confederacy".[1]

Biography

Early life

David Owen Dodd was born in Victoria, Lavaca County, Texas, to Andrew Marion Dodd, a merchant, and Lydia Echols Owen.[1][2] His Baptist[3] parents had married in a village south of Little Rock, Arkansas and moved to Texas where David and his sisters, Leonora and Senhora, were born. David's sister Leonora died before the Civil War.[2]

In 1856, the family returned to Arkansas and settled near Benton. In 1861, the Dodds moved to Little Rock to be closer to Senhora, who attended school in the city and lived with her aunt, Mrs. Susan A. Dodd. David Dodd went to classes at St. John's Masonic College. Dodd and his father moved to Monroe, Louisiana in August 1862, where Dodd began working as a clerk in the telegraph office, where he learned Morse code. His father traveled to Mississippi, leaving Dodd to stay with family and friends.[1][2]

In January 1863, Dodd went to Grenada, Mississippi and worked for his father who was operating a store. In September 1863, when the Union Army occupied Little Rock, the entire Dodd family moved south to Camden, Ouachita County, behind Confederate lines.[1][2][4]

Trip to Little Rock

As Union troops destroyed southern fields, tobacco was becoming scarce. Andrew Dodd devised a plan to buy tobacco and store it for later sale at a higher price. He looked to his business associates in Little Rock for the needed cash. Because Little Rock was in Union hands, he could not make the trip himself.[5]

Confederate General Fagan gave Dodd a pass so he could travel to Little Rock.On December 24, 1863, he sent David Dodd, a minor and therefore assumed neutral, to Little Rock to deliver letters to former associates seeking investments for the tobacco deal. Confederate General James F. Fagan issued the boy a pass. Dodd rode a mule to Little Rock, carrying a birth certificate showing he was an underage 17 along with his pass.[1][5]

Dodd stayed with his aunt, Mrs. Susan Dodd, in Little Rock. Except for some Union soldiers, there were very few teenage boys in the city, and Dodd was popular with the city's younger girls. He even became popular with some of the younger servicemen at the arsenal, especially because he usually was accompanied by a local girl or two. In addition to his father's letters, he also delivered letters to several people he knew.[2] Dodd attended some holiday dances with at least two girls, Mary Swindle and Minerva Cogburn. He also spent some time with 16-year-old Mary Dodge at her home, where Union officers were quartered. Mary supported the Southern cause; her father, R. L. Dodge, was a Vermont native on friendly terms with the Northern troops.[1][5]

On December 28, 1863, Dodd visited the Provost Marshal's office at St. John's College (several hundred yards southwest of the arsenal) and had no trouble obtaining a pass through Union lines to rejoin his family in Camden.[2] Dodd left Little Rock the next day. As he left Union territory, the guard tore up Dodd's pass since he would no longer need it now that he was in Confederate land. He went toward Hot Springs to spend the night with his uncle, Washington Dodd, southwest of Little Rock. The next day, Dodd traveled through the woods and found himself back behind Union lines.[1][5]

Arrest and trial

On December 29, 1863, Dodd was stopped by a Union sentry in west Little Rock, near Ten Mile House on Stagecoach Road, and was discovered to be without a pass. For identification, he showed his small leather notebook, where Union soldiers found his birth certificate and a page with dots and dashes. A Union officer was able to read some of the Morse code messages, which contained information about Union troop strength and locations in Little Rock; Dodd was arrested.[1][5]

The next day, Dodd was taken to Little Rock to face Brigadier General John Davidson, who was commanding the Union occupation forces in General Frederick Steele's absence. A telegraph operator translated the Morse code, which provided precise locations and strengths of Union troops. David was formally charged as a spy and was taken to the military prison on the site of the present Arkansas State Capitol building.[5] Dodd was interrogated for two days by Union officers who tried to discover the source of the information. On the third day, under personal orders from General Steele, Mary Dodge and her father were escorted under armed guard to a Union gunboat on the Arkansas River and transported to Vermont, where Mary was kept until the end of the war. This suggests that Steele had discovered that Mary Dodge was involved, and that he would not be able to hang a 16-year-old girl.[5]

On December 31, 1863, Dodd's trial began in Little Rock by a military tribunal of six Union officers. Brigadier General John M. Thayer presided with Captain B. F. Rice as Judge Advocate. Other members were Colonel John A. Garrett, Major Phineus Graves, Major H. D. Gibson and Captain George Rockwell.[5][6] The Court Martial lasted four days.[2]

The official charges were read by the Judge Advocate:

"In this, that said David O. Dodd, an inhabitant of the State of Arkansas, did as a Spy of the so-called Confederate States of America, enter within the lines of the Army of the United States, stationed at Little Rock, Arkansas, and did there secretly possess himself of information regarding the number, the kind, and position of the troops of said Army of the United States, their commanders, and other military information valuable to the enemy now at war with the United States, and having thus obtained said information did obtain a pass from the Provost Marshal General's office, and endeavor to reach the lines of the enemy - therewith; when he was arrested at the cavalry outposts of said Army - and did otherwise lurk, and act as a spy of the Rebels now in arms against the United States - This at the Post of Little Rock, and the encampments of the Army of Arkansas, on or about the 29th and 30th of December, 1863."[6]

To these charges, David pleaded "Not Guilty".[6]

On January 1, 1864, the trial continued with Dodd represented by attorneys T. D. W. Yonley and William Fishback, who was pro-Union and later became Governor of Arkansas. The defense attorneys proposed amnesty, which was rejected by the tribunal after an adjournment to deliberate the matter. Court was adjourned until the next day.[6]

On January 2, 1864, witnesses were called to testify against Dodd. Private Daniel Goldberg testified that he tore up Dodd's pass because "he did not need a pass anymore". Sergeant Frederick Miehr testified that he arrested Dodd after the boy could not produce a pass. 1st Lieutenant C. F. Stopral found Dodd's memoranda book, discovered that the Morse code reported the positions and armaments of the 3rd Ohio Battery and 11th Ohio Battery, and sent him to the guard house. Captain George Hanna testified that he interrogated Dodd, and discovered that Dodd was carrying one pocketbook containing Louisiana money, Confederate money, ten dollars in greenbacks, and some Confederate postage stamps; one postal currency holder, one loaded Deringer pistol, and a package between his shirts containing letters. Captain John Baird testified that, per Hanna's orders, he took the prisoner and the papers into Little Rock the next morning to General Davidson. Captain Robert C. Clowery testified that he interpreted the Morse code as containing detailed information about the locations and strengths of Union forces and armaments. First Lieutenant George O. Sokalski then testified about the actual Union troop strength and weaponry, which was a match of Dodd's coded message.[6]

During the trial, Dodd was asked several times to name the Union traitor who gave him the troop information; each time he remained silent. The defense tried to explain the Morse Code information as something Dodd did to exercise his telegraph skills. Dodd did not testify, although his written deposition was submitted.[5] Only character witnesses were called.[6]

By a 4–2 vote,[5] David Dodd was convicted of spying for the Confederacy and was sentenced to be hanged. He was taken back to the State Prison. General Steele designated Friday, January 8, 1864 for the execution day.[2]

Hanging

Union General Steele set the date for hanging.On January 8, 1864, David O. Dodd was brought to the grounds of his former school, St. John's, just east of the Little Rock Arsenal, for his hanging.[1] A crowd of five or six thousand gathered to watch the hanging.[7] Dodd stood on the tailgate of a wagon under the noose. The executioner, named Dekay, fixed the rope around David's neck, and the prop was knocked from under the tailgate. The rope stretched and the boy dangled, strangling to death over a full five minutes. Onlookers and Union soldiers became ill.[1][2][5]

The record is unclear about exactly how Dodd died. Some contend that one or two soldiers grabbed his legs to add weight and hasten his death. Others told that a soldier shinnied up the gibbet to grab the noose, twist the rope and raise the condemned off the ground.[1][5] Military doctors who examined Dodd's body reported death due to "a disrupted spine."[2]

Just prior to the funeral, Union Headquarters ordered no spoken or sung words at the memorial service, and that only Dodd's relatives in Union-held territory (two aunts and their husbands) would be allowed to attend. The town was tense; a riot was possible; there was fear that a Confederate raid would take advantage of the situation. Security around General Steele's Headquarters was increased; no one was allowed to see him except on official business.[5] Calm prevailed, and David O. Dodd was buried in plot Elm 355[8] in the southeast portion of Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock, in a grave donated by a Little Rock resident.[1][4] This cemetery was also the eventual resting place of R.L. Dodge and General Fagan.[5]

At a time when Union sympathies ran high in Arkansas and a constitutional convention was in session to enable the state to rejoin the Union, Dodd's execution fueled renewed divisions between Union and Confederate factions. Dodd quickly became a folk hero and a force behind renewed Confederate dissension.[7] After hearing the news of their son's execution, Andrew and Lydia Dodd spent the remainder of their lives in ill health. Andrew died of yellow fever in 1867, while Lydia died in Pascagoula, Mississippi in 1885.[5] In March 1864, General Steele was relieved of responsibilities in Little Rock and was replaced by a harsh anti-southern commander.[5]

Legacy

Dodd's story has been told in the poem The Long, Long Thoughts of Youth by Marie Erwin Ward, a full-length play and a 1915 silent Hollywood movie whose film has not survived.[1]

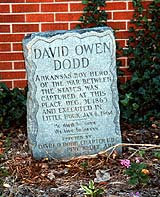

There are more monuments to David O. Dodd in Arkansas than to any other of its war heroes, including General Douglas MacArthur.[5] A monument marks the spot of Dodd's hanging, now in the corner of the parking lot of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock's School of Law.[5] Dodd's grave is marked by an eight-foot marble monument, engraved "Here lies the remains of David O. Dodd. Born in Lavaca County, Texas, Nov. 10, 1846, died Jan. 8, 1864." Nearby is a marble scroll with the words "Boy Martyr of the Confederacy."[1] David O. Dodd Elementary School in southwest Little Rock is located on land that was once a part of Washington Dodd's Farm. A stone marker on school grounds, believed to be the place where he was captured, was erected by the David O. Dodd Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and is dedicated to "Arkansas' Boy Hero of the War Between the States."[9]

In 1908, the Arkansas Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy starting raising funds for a stained-glass window in Dodd's honor. The window was built by the Charles F. Hogeman Company in New York City and depicts Dodd as Southern saint and martyr with curly blond hair, even though his only known photograph shows him with straight black hair.[5] The David O. Dodd window was unveiled at the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, Virginia on November 7, 1911 where it was displayed for several years. In 1988, it was found in storage and was moved back to Arkansas. The David O. Dodd window debuted at the Arkansas Museum of Science and Industry in January 1990. The Dodd window was returned to Richmond in 1998. In January 2004, the Museum of the Confederacy again loaned the Dodd window to Arkansas to commemorate the 140th anniversary of Dodd's trial at the renamed MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History (formerly the Little Rock Arsenal).[1][10]

Each January, the Sons of Confederate Veterans honor Dodd in a ceremony at his grave site.[1] In November 1984, the Sons of Confederate Veterans awarded the Confederate Medal of Honor to Dodd, one of only twenty-two persons so honored.[10]

See also

Biography portal

American Civil War portal

References and notes

1. "The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture". http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=2536. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

2."ASMS - The Story of David O. Dodd". http://asms.k12.ar.us/armem/montgom/dodd.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

3. "Documenting Arkansas". http://www.ark-ives.com:8012/cdm4/results.php?CISOOP1=any&CISOFIELD1=CISOSEARCHALL&CISOROOT=/docarkansas&CISOBOX1=Dodd. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

4."David Owen Dodd". Find a Grave. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=9825. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

5."Southern Heritage: Boy Hero of the Confederacy". http://www.southernheritage411.com/truehistory.php?th=086.

6."Online Little Rock Historic Places Guide, David Owen Dodd - Boy Hero". http://www.onlinelittlerock.com/content/historic/civil-war-david-o-dodd.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

7.Goss, Kay Collett (1993), The Arkansas State Constitution: A Reference Guide, Greenwood Press

8.34°26′33″N 92°10′01″W / 34.44241°N 92.1669°W / 34.44241; -92.1669 Location of David Owen Dodd's grave

9."Dodd Elementary School". http://www.lrsd.org/schoolindex.cfm?sccode=32. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

10."Arkansas Military Heritage". http://www.arkmilitaryheritage.com/exhibits/dodd.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-18.